Unka Kim's

Martial Art

bloggie thingie

bloggie thingie

send us an email

My cousin Mike Moon just published a book on a rehabilitation system he has developed called Deep Water Running. This program may be especially useful for the knee and leg injuries that might be suffered by martial artists. Mike has worked with athletes from the NHL, Rugby Canada and several other elite level sports. He is a track coach at UBC and has been a competitive runner for over 20 years.

You'll find his website at http://www.deepwaterexercise.com/

It occurs to me that the previous note was a bit cryptic. Allow me to expand a little on teaching in the martial arts since I've been thinking about it.

It's a pain in the butt, always has been. I've never had enough instruction around to allow me to simply be a student. The Aikido club at the University of Guelph was started in 1980 by Peter Yodzis who taught twice through the week as a third kyu. Bruce Stiles came up from Toronto once a week on Sundays to teach a class. As a result I was doing some of the teaching within a couple of years, maybe from third kyu.

The same thing happened when I started teaching iaido formally at the University in 1987. I went down to Toronto to study with my instructor (Goyo Ohmi sensei) and brought back what I had learned to the students here in Guelph. There wasn't any grading in iaido until 1991, some 8 years from my first lesson, so I was practicing and teaching for quite a while without any rank at all.

The rank doesn't matter, but the teaching certainly does. There are many students of budo who can't wait to start teaching, figuring that this is the ultimate goal of their training. After all, sensei gets to tell folks how to train and seems to know it all so hurray when we get to teach. We're a big cheeze now!

These folks are, I'm afraid, almost always a real drag on the system and not good instructors. The desire to teach is, in that most Platonic of ideals, a big recommendation against teaching. Teaching slows if not entirely prevents your own progress in the art. It is also the place where you start getting into all the nasty grimy stuff like finding a place to practice, dealing with landlords or administrations, and finding continuing instruction for yourself and for your students within a larger organization that is inevitably as hard to get along with as all organizations are.

Like I said, a pain in the butt.

But at some point you usually need to start teaching, often out of necessity when you move away from your teacher, sometimes because the art is very small, or eventually because you are simply the "last man standing" and you outlive everyone above you in the hierarchy. Yippee for those who avoid this until they're 6 or 7dan, as is the case for many in Japan, but here in the west it's unusual for a 5dan not to be teaching.

When it finally happens and you're out there in front of a bunch of beginners looking at you like you're some sort of intelligent being, you want to do your best for them. You want to do your best for the art. You want to teach as hard and as well as you practiced while you were a student. You want to survive until the beer at the end of the class.

If you're very, very lucky you will teach long enough and have students who are smart enough to become better than you are. Those students will take the art forward to something better than it was when you started practicing.

Despite teaching way too early, and having to grab instruction where and when I could for myself, despite not being as good at this stuff as I could have been if I'd had a sensei to kick my ass four or five times a week while I was in my 20s and 30s, I have some of those students.

And that's something to have a little gloat about.

I'm not really all that good at Iaido, or Jodo. Nor was I all that good at Aikido for that matter.

I'm not better now than I was, I'm getting heavier, the joints are wearing out and my techniques are starting to look a bit "old man", but none of that bothers me much.

You see I've got students out there that are better than I am. I have students with me now that will be better than I am one day. Many of these students are now teaching and have every chance of having students that are better than they are.

That's the thing that keeps me going in this stuff, seeing the art grow, seeing the students "get it" and watching them as they pass me by, protesting every moment that they'll never be as good as I am.

Delightful liars. You gotta love them. The only thing better has been watching my own kids grow up and find their own way of being better than the old man.

It occurs to me that I teach in two different ways when I'm teaching the martial arts or self defense.

In the martial arts I can take a long time with each student, usually years, to get them as far along the path as I can. I can let them set their own pace, and respond carefully and thoughtfully to their needs along the way. Once they are at a certain level, both mentally and physically I can give them a shove to get them to the next level. This can often seem a cruel process, involving perhaps a bruise or two (on both sides), but it rarely results in the student feeling bad or quitting if I've done my work correctly.

Teaching self defence is another thing altogether. In that case I'm taking a large group of women and, over the course of 10 weeks, getting them into a place where they feel they can resist an attack. I need to get them quickly to a place where I might take several years to get a martial art student. In one case the process is physical with a concentration on good technique, in the other it's almost entirely mental. With plenty of time I can teach the fine points of fighting to a martial art student and let the confidence of that skill soak in to affect their mental state. In the case of the short-term self defence class I have to switch the mental processes around so that they can give themselves permission to resist an attack. This has to be done quickly since we don't have years to correct mistakes and a small slip can result in an entire class being no better off than when they came in the door.

This is something that most martial artists don't understand about self defence classes. The emphasis on fighting skills and the conviction that you can't learn how to fight in less than several years will prompt martial artists to doubt the effectiveness of short courses. Fortunately, the research on assault and resistance suggests that being a harder target, resisting in just about any way imaginable (except begging, crying, pleading and of course not doing anything at all) works. The point is to get the women efficiently to a point where they can give themselves permission to resist.

The cruelty in a self defence class becomes quickly apparent when someone has an injury, is suffering from mental doubt about their own ability, or is simply moody. As an instructor with a room full of semi-trained women who are seeing the material being taught for the first time I can't step out of the teaching role to take care of individuals, and I can't allow the energy of rest of the class to be dropped by that individual. As a result a student occasionally gets left behind as the class moves forward. If they have an injury, a pulled muscle or twisted ankle perhaps, the usual procedures are applied, Rest, Ice, Compression and Elevation, but they are applied by an assistant or a fellow student. If the injury is more severe as has happened once in the twenty years I've taught the course (a pulled abdominal muscle while running), the professionals are called in and the rest of the class moves on.

Injuries aren't a frequent problem, and a certain amount of bruising and muscle soreness often becomes a mark of pride. Self-doubt, fear, internal chatter and just plain whining are the more usual problems in a self defense class. Cruel can seem the response to these problems. As an instructor I will usually confront the student verbally, and perhaps physically challenge them to see if I can solve their doubts, cure their fears or stop their internal monologue quickly. If that doesn't work they have to be left behind to deal with their own problems as the class as a whole must move along. The good instructor will still be looking for a way to bring that lost soul back into the class but occasionally they simply drop out and we can only hope they got something from what part of the class they attended.

In a martial art class the instructor will usually deal with physical injury and especially with mental problems personally, showing the care and concern of a parent while letting the rest of the class get on with some self-directed practice. In the self defense scenerio that parent gets replaced by the drill-master by necessity. The rest of the class can't be left to stand around getting cold while the instructor takes care of one person's bruised shin or ego.

So what have I just suggested... simply that martial arts students are often coddled and chided along while believing that they are being treated roughly (for their own good). On the other hand, the women in self defence classes are being pushed hard in order to make them push back from a position of inner hardness. Pushed in a way that would likely make a martial art student quit in disgust at what a jerk their sensei was.

Reading that over it sounds much more dramatic than it actually is. I suppose the baseline is that in the martial art class we're teaching individuals, while in the self defence class we must teach to the masses and sometimes that means the individuals get left a bit behind.

From time to time the discussion of who can teach the martial arts comes up. Quite often the talk turns to the "Japanese bias" of students, where they will tend to assume that anyone from Japan is a sensei, and all Japanese, despite their rank or skill level, are more knowledgeable than Western instructors.

I think the bias is something that anyone who hangs around long enough to start teaching this stuff runs across eventually. The thing is, we had it ourselves when we started. It's not really all that much of a problem, since everyone who sticks around for 20 years comes to a better understanding of the difference between race and talent, but it can be annoying and in some cases, for instance in arranging seminars with local instructors, it can be a problem.

Beginners like the exoticism of a Japanese martial art so of course they are going to like the experience of being taught by a Japanese sensei. It's just a natural reaction, the same desire for a foreign flavour that took you to budo in the first place is going to incline you toward a Japanese instructor. There's nothing wrong with that, especially if what you're after is a cultural experience.

This same search for the exotic will lead to such assertions as you have to be in Japan to learn a koryu, that you have to understand modern Japanese culture in order to really understand a 400 year old martial art, and that anyone who has gone to Japan suddenly gets "touched by the kami" and knows some secret.

Western instructors often play this up as well, making a fetish of their time in Japan, their access to the Japanese sensei and implying that they have certain secrets that they can impart. This helps perpetuate the assumptions and is mostly harmless if the students are only after the exotic.

It can, however, be a problem if students are serious about the arts and are preventing themselves from learning by not listening to Western instructors who are both experienced and local. By ignoring these sensei the students are losing a valuable and regular source of training.

The Japanese themselves understand this problem, and there are several here in Canada who recognize and lament the rather silly assumption that a Japanese instructor is worth more than a Westerner. This is apparent even in what you can charge to attend a seminar with a Japanese (even if a local Japanese) instructor compared to a non-Japanese instructor.

In Canada we've been lucky to have many Japanese issei and nisei instructors who have no respect whatsoever for the idea that "being Japanese" implies superior skills. They are as happy to see a westerner sweating on the floor as they are to see a Japanese, and more importantly, just as frustrated with a Japanese who won't give it their best at practice. In other words, we get over the Japanese thing earlier here because we are exposed. In other places with no Japanese population I've seen more than one cult grow up around westerners who have "talked to Japanese".

The fact remains, whichever budo we practice, it's a Japanese art and while there are many westerners who are quite good at kendo, iaido and jodo, there are many more senior Japanese sensei out there. We would be as foolish to ignore them as we would be to ignore senior Western instructors in our own countries.

The beginners will always believe that any Japanese has great skill in Budo, just as, I am sure, the "man on the street" in Tokyo believes Canadians know about hockey, Americans know about 6-guns and Europeans know about football. We should simply accept this and move on, confident that anyone of any nationality will eventually be skilled in our chosen arts if they continue to train for a couple of decades with good instructors, regardless of where they were born.

Quite a while ago we had a "shoto seminar" where we examined the short sword techniques from the kendo no kata, Niten Ichiryu and Muso Jikiden Eishin Ryu. The following question came out of the seminar and I thought I should finally try to answer it.

Since the seminar we had here

I've been thinking about tenouchi. In particular I've been thinking

about

tenouchi for one handed strikes since I practice Jodan no Kamae. A few

of the "whys" you gave during the kodachi Kata about how the wrist

works, etc.. have gotten me thinking on how I am doing tenouchi when I

strike.

Cutting out all of the details that I've been going over from what I know, think I know, saw at the seminar, etc... I was wondering if you could give me an explanation on how you particularly do tenouchi when you do a one handed strike in Iai...

...and perhaps how you think you would do tenouchi if you were to do one handed strikes with a shinai fighting in Bogu.

I've been focusing on what I do with my thumb; how and where I move it, how i squeeze with it, etc. And similarly for the wrist; how it bends, torques, flexes, moves, and where.

Cutting out all of the details that I've been going over from what I know, think I know, saw at the seminar, etc... I was wondering if you could give me an explanation on how you particularly do tenouchi when you do a one handed strike in Iai...

...and perhaps how you think you would do tenouchi if you were to do one handed strikes with a shinai fighting in Bogu.

I've been focusing on what I do with my thumb; how and where I move it, how i squeeze with it, etc. And similarly for the wrist; how it bends, torques, flexes, moves, and where.

First, let me define tenouchi and shibori as I use them. Tenouchi is how and where you grip the hilt of the sword and pull it into the palm of your hand. Shibori is how you twist your two hands together when you cut.

On grip, you can check out the articles here http://ejmas.com/tin/tinart_taylor2_0100.htm and here http://ejmas.com/tin/tinart_taylor1_0300.htm which explain a couple of the concepts behind a two-handed and one-handed grip.

On to the thumb and the squeeze. I have tried to take some shots of myself with the point and shoot on timer, forgive the ugly backgrounds.

Here we have a recap of the grip.

fig 1. two handed grip

fig 2. angle on palm of two handed grip

fig 3. If we move the angle to a more square position across the palm we get the one handed position.

fig 4. one handed grip

fig 5. for comparison, here is a one handed grip using the two-handed position across the palm.

In this last shot take note of how the wrist turns off to the side of the hilt naturally. To hit with this grip would mean that the blade would not be lined up with the arm and a lot of power and speed would be lost trying to keep the edge on line by torquing the forearm. The more square grip puts the wrist directly over the hilt.

fig 6. This is the classical "ping pong ball" grip, whereby a ball would not fall off the hand if placed on top. I have seen this in books and heard it taught.

fig 7. This is the "straight thumb grip" that I recommend for one handed grips. The thumb falls straight down the side of the hilt, in line with the edge of the blade. You can see that this grip again pulls the wrist over the hilt and puts the forearm in line with the edge.

fig 8. Tenouchi

fig 9. Shibori

When it comes to the actual strike we may want to pull up with the thumb, into the palm as we also tighten the index finger. This is especially tempting with one handed strikes but as you can see in fig 8 above this will tend to twist the edge offline and roll the hand inward where it may even collapse. By squeezing the thumb sideways rather than pulling upward as in figure 9 we see that the wrist again moves over the hilt and the edge of the blade stays on line.

If you would take a small test for yourself now we can make a final point on grip strength in one handed strikes. Grab anything in your hand and roll your fingers inward as if gripping in fig. 8. How easy it is to keep a strong grip with your fingers? Now roll your wrist inward, driving the thumb down and the fingers outward. What happens with the grip?

For me, the way my fingers work, I can keep a grip on the hilt if my wrist bends outward, but when it bends inward (as if trying to touch my wrist with my thumb) the fingers naturally open.

Finally, by pulling up with the thumb and forefinger we are actually slowing down the strike. In a one-handed swing the tip is accelerated by the muscles of the forearm through the leverage from the little finger to the base of the index finger. If we pull up with the index finger and thumb we remove the forearm from the swing and it all comes from the extension of the arm and the shoulders. Much slower tip speed.

I hope, with the previous two articles, that this gives folks something to think about at least. The best advice of course is to try this out and see what works for you.

Beginners worry.

They research, look at other students, look at other sensei, look online and find videos. They find stuff that doesn't look like what they're doing so they worry they're doing something wrong.

Often they start to worry that their sensei isn't doing things right. Questioning sensei is great, a necessary step in our progress once we're far enough along, but take it too far in your own head and you're out the door looking for someone who looks like that youtube video you saw.

Feet fascinate students. They really get into foot positions, probably because sensei tells them that it all starts with footwork. Students worry about what angle a foot must be, is it 45 degrees, is it on the attack line, is the rear foot at 90 degrees to the front? What they need to learn, and what they will learn eventually, is that the foot is just an indicator of what our hip is doing. We really need to worry about our hip, learn what our hip should be doing at each stage of our movement, and the feet will follow. Unless we're duck-footed or pigeon-toed.

These worries are especially easy to develop when we're practicing koryu. Unfortunately trying to figure out what your line of koryu is doing correctly or incorrectly by asking what other lines are doing is like trying to figure out what Tiger Woods is doing right or wrong by watching Jack Nicholas. There isn't a correct or incorrect in most koryu any more since the founder is dead. It's all a big argument about who's closest to the "original teachings". We can agonize over who's closest to some past headmaster or whether or not we're studying under the current headmaster but again, rather pointless. Most of the koryu in the West are now too big for a single headmaster to deal with, too many lines of practice.

Even in a tiny art like Niten Ichiryu you get arguments and lines fracturing.

But the bottom line is that at the end of it all the art fits the man, not the other way around. That's a big secret that takes a lot of years to learn so most of you reading this should probably put your hands over your eyes.

It comes down to "I don't look like my sensei.... why?"

That's your starting point right there, not "why doesn't my sensei look like those other guys" but "why dont' I look like sensei"?

I'll leave it up to you to make a list of reasons for yourself. Have a good look at it.

I have had several students head off to Japan over the years, and of course have read lots of advice on the net that you can't learn the martial arts without going to Japan.

It absolutely used to be the case that you had to go to Japan to learn Judo, Karate, Kendo, or any of the other Japanese arts which did not exist in North America, but I seem to recall that the last World Championships of Kendo were won by the team from Korea with the USA taking second place. Japan took third with Chinese Taipei. Eventually, every Japanese martial art of any size has been exported successfully to other countries where it is learned and taught without the need to go to Japan to study.

Are there good instructors in Japan? Top competitors? Absolutely. Should the top folks in any martial art practice in Japan? Probably, or at the very least they should practice with the top instructors from Japan. However, it does not seem to me that it is necessary to go to Japan to learn a martial art if that art is being taught by competent instructors in your home country.

In other words, if the art only exists in Japan, you must go to Japan but if it is not taught exclusively in Japan it would seem you have a choice.

Not only that, but I have had students head over to Japan and then complain that they can't find any instructors near where they end up teaching English. They now practice less than when they were in Canada. Of course that can be remedied but again, I have had more than one Japanese student join our class and comment that there was more opportunity here to practice different martial arts than back in Japan, either because of distance or because they had more access to top instructors here than they would have in Japan.

So why the attraction to Japan? It seems that some folks believe that you must go to Japan to learn "in the culture" of the samurai or at least the culture of the originators of your martial art. I've always had a problem with this, the general culture of Japan is no more attuned to the samurai than the culture of Alberta is attuned to the sodbusters, or that of New England is attuned to the whalers. Unless you can soak up past cultural knowledge from the landscape I have my doubts that you can do it from mining the modern culture for those remnants of the past that still cling.

While it may be true that Japan has remained rather more homogenous than Canada or the USA, I would still not expect that the modern Japanese would be any more in tune with an Edo period swordsman than a modern German would with a longswordsman of the same era. Despite Germany being a lot more homogenous than the new world countries. We just don't carry that much forward from our past when it comes to our everyday culture.

Think about how similar your life and belief system is to your grandparents.

If you're going to go to Japan to learn the culture, that's great. If you're going to go learn the martial arts in the modern culture of Japan, that's even better. Going to Japan to learn the martial arts in the same culture in which they originated? Perhaps a little bit more difficult.

Don't think I've got anything against going to Japan to study, I really don't. I just don't understand the attitude that you can't learn the arts elsewhere. In fact, I can see a real benefit to going to Japan and studying full time, the same benefit that a monk gets in a monestary. It's easy to meditate in the temple, and difficult to be a monk in the world. If you can find a situation where you can practice the martial arts full time and concentrate without distraction, you've got a great chance to learn.

On the other hand, if you are in Japan working, worrying about your next visa, trying to communicate and find your way around and generally fighting all the same distractions you face back home, your progress in the arts may not be any more rapid than if you had stayed home and kept studying with your teacher.

Living requires the same attention and demands the same payment no matter what country you're in.

One of my students told me the other day that his former teacher told him not to practice the techniques he was learning at home because he might develop bad habits that he'd have to change later.

A couple of the seniors winced and one of them told me to sit down before I even started to comment. OK I may get a bit heated about a couple of things, and this is one of them.

Only in the martial arts have I ever heard this advice and I'm darned if I know where it came from. Can anyone imagine a violin teacher, a dance teacher, a language teacher or any other instructor you can think of telling someone not to practice on their own?

It's just unimaginable to me, but I hear it over and over again. You may develop bad habits!

Folks you won't develop any habits at all if you don't practice, but hey, habits aren't all that good an idea when practicing the martial arts, what you want to develop is an understanding of the art you're learning, not a bunch of reflexes that an opponent can trigger and then use against you. To go home and practice something in one way, come back to class and be told to do it a different way, is a good thing. It will prevent reflexes and habits.

Yes, we tend to be comfortable with what we learn first, I've proven this over and over with my self defence classes where I teach each new bunch to roll on the right side or the left side first depending on my mood. Whichever side I start them on they are most comfortable with for a while. But always, with practice they even out and it doesn't matter, or they go to their natural side. Yes what we learn first tends to be what we favour as a beginner, but all that says is that if we know how to do it one way, we know how to do it that way.

So what? If we can learn one way we can learn another, and another.

It's hard enough to keep students around without discouraging them in their first flush of enthusiasm, and it's DAMNED hard to get students to practice enough to become good at these arts so why would you stop them from doing it?

Makes no sense to me at all.

Important news for those conducting scholarly research in

martial traditions:

2009 Scientific Congress on Martial Arts and Combat Sports

will take place on 16th and 17th May 2009, in Viseu (Portugal).

Anyone interested in attending or presenting a paper or poster at this congress should contact: Dr. Abel Figueiredo, Email: namban@netcabo.pt

GOALS

MAIN TARGET GROUPS

2009 Scientific Congress on Martial Arts and Combat Sports

will take place on 16th and 17th May 2009, in Viseu (Portugal).

Anyone interested in attending or presenting a paper or poster at this congress should contact: Dr. Abel Figueiredo, Email: namban@netcabo.pt

GOALS

- To gather researchers in order to promote debate around the study object of the contexts of 'martial arts', 'combat sports' or 'personal defence': combat human motricity;

- To reflect on on-going national and foreign research work;

- To promote the dissemination of projects in the fields concerned;

- To call the attention to the need of developing different scientific approaches.

- Researchers in the field of martial arts/combat sports;

- Teaching and training technicians in the area of martial arts/combat sports;

- Higher education students and advanced level practitioners;

- Heads of Organisations promoting martial arts/combat sports.

I see our neighbours to the south have a new leader, and I see that the Globe and Mail has headlined part of his speach.

What is required of us now is a

new era of responsibility - a recognition, on the part of every

American, that we have duties to ourselves, our nation, and the world,

duties that we do not grudgingly accept but rather seize gladly, firm

in the knowledge that there is nothing so satisfying to the spirit, so

defining of our character, than giving our all to a difficult task.

It's interesting that the analysts don't see this speach as having a "famous line" on the same level of "fear itself" or "ask not what your country", because I think that call to responsibility is a pretty radical idea.

Consider the entitlement society we have developed over the past generation or two, the culture of victimhood and expectation that has produced warnings on coffee cups about hot liquid, and the absolutely meaningless warnings on television programs about "strong language". In an era where absolutely nothing is our own fault, where we aren't expected to take care of ourselves, where we actively hunt for someone or something else to blame for our own shortcomings, a call to responsibility is a pretty radical cry.

What connection does this have to the martial arts? A very strong one, the arts are about personal responsibility, about taking charge of our own defence and by extension of our own lives. The martial arts are about the obligation to act and the acceptance of the consequences of those acts.

Radical indeed, worth thinking about and certainly worth the hope that some will listen.

There is a little bit of a discussion on Kendo-World about the jodo kata Ranai. It was triggered by a youtube video and there were some comments about differences between this kata as done by students of the Jodo Federation and what is done by the Kendo Federation (Jodo section of course).

The differences are visible, and seemed quite large to me at first but on second look they were really such things as the sword moving the jo out of line provoking an attack as vs the jo simply moving to attack again.

One comment was about some small steps which may or may not be there in the kata, in other words "Is that a real difference?"

Interesting question on a couple of different levels.

1. Was that something that particular jodoka did only in that film or is it something in the kata as he practices it? Watching youtube videos should always be done with this question in mind. Looking at someone doing a kata once on film may show you a perfect example of the kata, or it may show you a few mistakes that are so skilfully moved through that you are getting a perfect example of an "incorrect" kata. Both these possibilities are there when you are looking at advanced students. Of course you may also get something that is obviously flawed, in which case you are probably looking at beginners and everything should be taken with a grain of salt.

2. Is it a real difference between two lines of practice? Is this done in this line and that done in the other line and perhaps a third thing done in yet another line?

How much difference makes "a difference"? If one line takes an extra step and another does not, or a full step in one organization and a half step in another, is this a real difference?

This is going to depend on whether or not you're talking to a beginner. For a beginner there is only one way to do a kata. One correct way and that's the way the beginner was taught. A half step vs a whole step is a difference, and, since a beginner can't judge what's important and what's not, it's an important difference by default.

On the other hand a senior may well look at you with a puzzled look when you ask about the difference. He might say "it depends on how far away the other guy is" or he might say "never thought about it, I suppose you could do it both ways". What is a real difference to a beginner might not even be noticed by a senior.

3. What's a real difference to a senior? Now there's the important question and it may well be answered in such areas as timing, intent, feeling and intuition, things a beginner can't even detect.

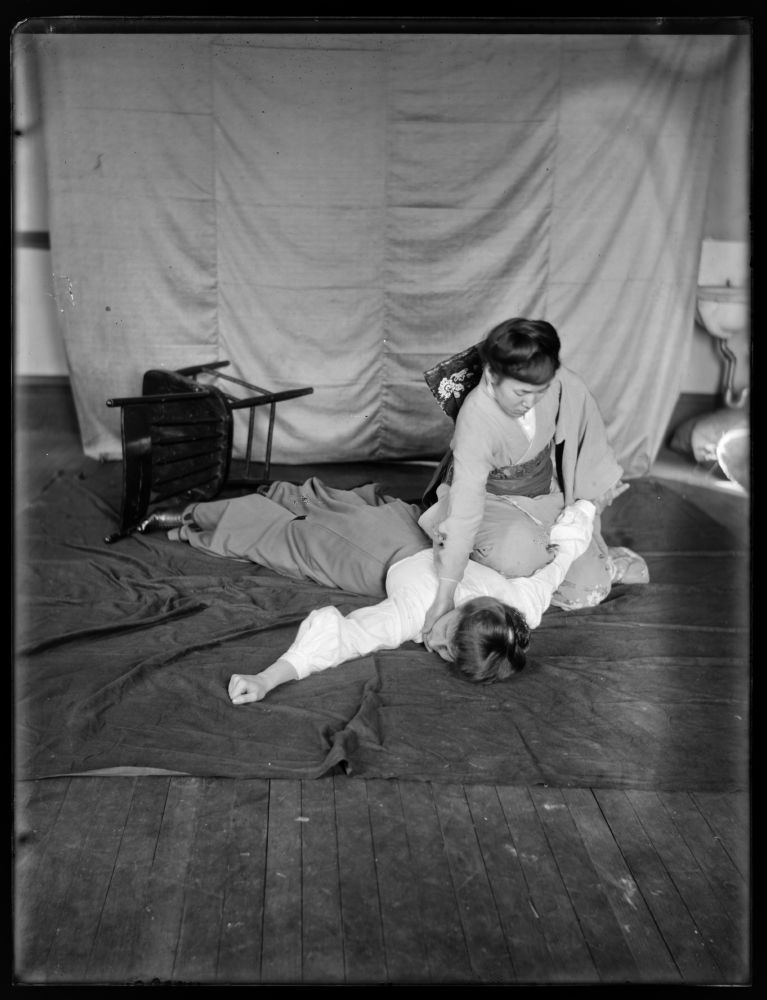

Flickr has a searchable photography archive at it's "The Commons" location which is unencumbered with copyright and licensing rules. Regardless of that, it's a source of historical material.

Here's a woman doing jiujitsu that's interesting to me in that the photographer tried to create an on-location photo studio by hanging a couple of drop cloths. Unfortunately, as I've found myself, martial arts practice tends to move beyond the desired frame very quickly and we're treated to the sink on the wall in the background.

I'm also rather fond of the term Jiu Jitsu which would be jumped on big time in any martial art forum these days, the experts would be quick to correct the unlucky poster. Well it's part of the history of this photo so no changing it!

Wikimedia commons would be another place to go looking.

William M. Vander Weyde (American 1871–1929)

Title: Jiu-Jitsu for Women

Date: ca. 1900

Medium: negative, gelatin on glass

Dimensions: 8.5 x 6.5 inches

George Eastman House Collection

General – information about the George Eastman House Photography Collection is available at http://www.eastmanhouse.org/inc/collections/photography.php.

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

A student was asking about unarmed martial arts last evening and I mentioned the Aikido club, which is a very good one here at the University. One of the fellows who teaches was at the very first workshop in 1980 which is also when I started. I drifted to iaido and jodo after I tried it out for a decade, but he stuck with it and got good at it.

The response was that a friend had done the class for three or four weeks and quit because while the instructors were very good the students were all "blind leading the blind". In other words, it's a University club, perpetually full of beginners. Beside that though, Aikido was "a bit soft" nowadays, with folks spinning around two or three times before throwing.

Fine I said, what about Judo?

Tried that but what if the guy doesn't have a gi on?

This went back and forth for a while. Eventually he mentioned he'd like to do some good koryu jujutsu and said there was one fellow he'd heard about who was supposed to be doing the most authentic stuff around and I asked what it was. "A combination........"

Right there I knew we were talking about apples and oranges. He couldn't remember all three arts the fellow did but the first was a thoroughly modern form so I launched into an explanation of what koryu jujutsu is and why he wasn't interested in it.

It's old. It's full of techniques to deal with folks who are wearing armour, or attacking with a sword or a stick. It often assumes the defender has a knife tucked away in the front of the belt. It often involves even more little weapons that would be positively silly to have about your person these days.

But worst of all, it's done in kata. I suppose some styles have randori but one doesn't practice the way one practices modern judo, aikido or jujutsu, by kihon and randori, one practices by kata. Full setpiece fights from start to finish. A limited number of them, no new ones, no adjustment or discussion of applications in the modern age, no adaptation to modern clothing, just kata.

I may be simplifying but you get the idea. Koryu jujutsu is something you should probably practice for any reason EXCEPT effectiveness if you're looking for an effective jujutsu.

Much better to go with something that you can practice anywhere, and that you can run a quality test on.

Judo for instance. A judo instructor will look pretty good to anyone who walks in off the street, but if you're there a week and you see the fellow getting trashed by a green belt, then a week after that by a blue belt (assuming they are serious matches of course) you can pretty much assume your instructor may not deserve his black belt, or may be past it. What I mean is the competitive sports (judo and kendo) are pretty hard to fake, you can either perform the techniques or you get your ass handed to you. There isn't much room for BS.

Yes but they're just sports.

Yes they are sports but there's no reason anyone should get all worked up about winning and losing and doing all the little sporty things like muscling a throw or dodging a shinai so it hits you on the shoulder instead of the head. Compete purely and cleanly, have your ass handed to you for years and years and say thank you after each defeat. If beginners really listened they'd hear their sensei telling them that anyway (the ones who are of high enough rank that is). After enough time your ass may not be so easy to beat.

Aikido all big and soft and swirly? Sure it is for practice and for beginners but trust me, there are some nasty things in there if you pay attention. Anything big and slow can get small real fast.

Can't punch someone in Judo? Well no you can't in class or in a match, but who says you can't on the street? It doesn't take long to learn how to throw an elbow. No judogi? So grab his shirt. If by some strange circumstance you're fighting someone who is naked, grab his hair, or lock your hands around his neck, or hook his arm....

In a few years you won't be practicing any art for effectiveness and self defence anyway. Waste of time, you learn all the nasty fighting techniques in about 6 months and from then on it's just practice for the next fourty years.

Still interested in the koryu jujutsu but want effectiveness? How about six months of judo and then forty years of koryu kata.

No, better yet, six hours of judo and four hours of koryu jujutsu per week for forty years.

At this point in the kata he knocks your hat off with his sword.

This makes you really mad so you grab a stick and...

(photo by Colin Pitman)

My sensei has quit teaching at least once a year for the last 15 years, and now is talking about being allowed to retire honourably.

I get it. I really do.

All the University students are back at the gym, I've got a demonstration tomorrow morning (looks like me and maybe our newest beginner if he remembers to show up) and it just occured to me that the two seniors who have been running interference for the club with the administration may both be gone next year.

Not for the first time I'm feeling like I'm just too old for this stuff. All I ever wanted to do was practice, I never wanted to teach and only ever did so because I needed bodies with cash to get a practice space and teachers from Japan for my sensei. I sure never wanted to do all the organizing and...

Well let's face it, I'm now old enough that I just don't want to be bothered with remembering where I have to be. I've been here, there and six other places every day at a certain time for half a century and I'd like to be noplace for an unspecified period of time, with no need to worry about who's going to do this or that next week.

Quitting time? I totally get it.

Here's my dream for the never-to-be-here future, I own a dojo that would be open from 6am to 9pm for anyone to come practice at any time. I wander in whenever I feel like it and help anyone who's there. If there's nobody there I practice.

That's it..... no wait, my knees work again. Better get that in just in case the budo gods are paying attention.

I run a martial art supply business for those who don't know, that's it up in the right hand corner of this page. Many years ago the business sold iaito (practice swords for iaido) that you could customize, pick everything and our partners in Japan would make it for you. That got to be a real pain in the butt when orders went to many weeks and then months before getting filled, and then the business we dealt with decided to pack it up. I wasn't too upset and we simply moved to bringing over generic blades from good makers. Solid equipment that wasn't anything special to look at but worked fine. We sell as many or perhaps even more iaito than we ever did.

Folks still get in touch and ask about customization and I just pass them along to Brenda since I really haven't a clue what they're talking about. I thought perhaps I'd explain why I'm not the one to talk to about fancy equipment, even though I sell it, and still make fancy and custom wooden weapons.

The long and short of it is because of the way I was trained in the martial arts. Starting in 1980 I have simply used whatever was in hand. My very first wooden weapon was handed to me by my Aikido teacher with the words "here, this is a good one, you owe me $35" I still have that bokuto around somewhere I think. Shortly after that I started making them myself and have never stopped. I used to charge $15 for one of my bokuto but when I found my fellow students were using them to dig cars out of the snow, pound nails and were more or less treating them as disposable, the prices went up. Nothing to do with customization or the worth of my craftsmanship, just a way to avoid having to spend so much time in the shop.

When I started to practice iaido I began with a bokuto and then bought the only thing I could lay my hands on that had a saya, a plastic hilted wall-hanger. Heavy, no balance, no hi, those things were cheap and more than a couple of our students started with them. The rule of thumb eventually worked out to using one of those monsters until you snapped the hilt in half, then you bought a proper iaito.

For myself I continued to obtain blades in a pretty off-handed way, mostly by someone handing it to me and saying "you need this, give me this much money for it". The first non-wall-hanger blade I used, and the one I learned most of my iaido with, was a WWII shinken that had a hi ground into it freehand using a router in an attempt to lighten it up. The thing was sharp, in a really chewed up saya, with a wrap that was falling off. I re-wrapped it myself with leather and it eventually got passed along to a couple other students before disappearing into someone's closet.

After that one of our sensei from Japan took pity on us and brought over four identical iaito, two at my proper size of 2.6 shaku for myself and another student, and two others for a couple other students. No choice in the fittings, just "pay the man".

I used that one for a lot of years until some student or other said he had to have it, so I sold it to him and started using.... I don't know what I was using then, maybe a bokuto. Perhaps I went back to a shinken since around then I had a couple made for me, one from a knifemaker in the States who has since passed away. That blade was fitted out by a local craftsman with iaito fittings but I couldn't tell you what they look like. I think the wrap is green leather, or is that the papered shinken from Japan?. I also had a blade forged for me by the fellow who teaches the smithing courses we present, and it was fitted by another local craftsman. When he asked me what menuki I wanted in the hilt I said "put a couple of copper slugs in there so it looks OK from a distance. That's what I've got, fuchigane and menuki of plain copper.

Some time around then I mentioned in a seminar that I needed a good 2.6 iaito again. A couple months later a fellow who sold them (who was at that seminar) handed me an iaito and told me what I owed him. I used it for quite a while before someone said "so what fittings do you have on your iaito"? I had to go look.

Some time after that I ended up using a 2.7 blade when I took it off a student during a seminar because he couldn't handle it, and handed him that 2.6. That 2.7 went to another student of mine for a few years because he needed to get bigger in his movements and I switched to a shinken. That one was sold to another student who was trying it out and managed to bury it in a beam at the dojo. I got the shinken I use now because it was one that Brenda wouldn't sell due to a nick in the wrap... I put some crazy glue on it and have used it for at least 3 years now. I think the menuki are koi and I'm pretty sure the tsuba is a Musashi sea-cucumber. I know it's black with a black polyester sageo because I haven't managed to put a nice silk one on it. May not ever replace that sageo because the polyester is tougher than the silk and I dug the shitadome out of the kurigata. It may never wear out.

And that's why SDKsupplies doesn't mess around with selling custom iaito. Tell me what length you need, I'll hand you one and Brenda will tell you what you owe us.

Happy New Year.